I’ve been taking online classes recently, in a variety of unfamiliar styles, from the comfort of my living room. A friend remarked that he’s surprised at how I manage to learn so well without a mirror – his surprise surprised me. I never used dance mirrors growing up: all my formative training took place at home, in community spaces, and on the stage; I didn’t step into a “fully equipped studio” until I was 19. This isn’t special or uncommon either. Plenty of dancers primarily learn and practice outside of studios, proving the case that a mirror is not necessary for dance.

So I’ve been thinking about this mode of learning, as well as the general history of Sri Lankan dance education, against the ubiquity of mirrors in dance studios. Mirrors are so central to “professional” training now, particularly in the European classical tradition, but increasingly in other contexts as well. According to Sally Raddell, since their emergence in ballet training of the 18th century, mirrors in dance studios have become the “primary mode of information gathering.”

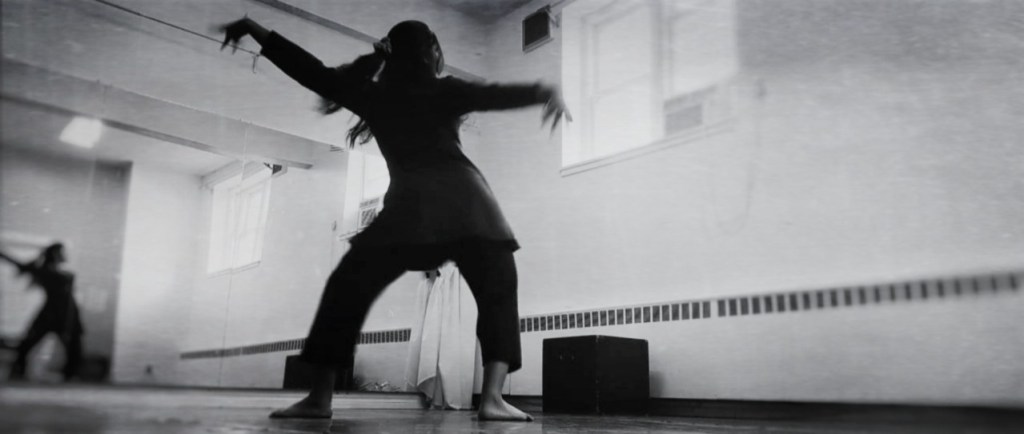

In contrast, traditional Sinhalese dance training favoured, I would argue, non-visual modes of self-awareness. Our traditions speak of daeka purudda, aaha purudda, kara purudda (“habits of seeing, hearing, doing”) – a pedagogy emphasizing practice, muscle memory, and embodiment, rather than visual ideals. Susan Reed, writing on how traditional Sinhalese dance is taught through demonstration, calls this “knowledge transmission based primarily on mimesis” – but the concept of imitation centralizes the idea of the image. To shift that focus, I would add that, given an absence of large mirrors in Sinhalese villages, traditional dance education involved imitation without visual self-verification. Having only the body as its own reference, dancers would have to rely on internalized modes of immediate feedback and self-verification to effectively see themselves without actually seeing themselves; they would need to focus on developing an attention to the spatial positioning of moving bodies (developed through kara purudda) in relation to temporal rhythms (developed through aaha purudda).

Kinesthetics calls this kind of non-visual, bodily self-awareness proprioception. Raddell considers this “felt understanding of exactly where one’s body is and what it is doing” a “critical ingredient to being [an]…expressive dancer,” and notes that mirrors may delay its development: “The image students see…in the mirror and the feedback it provides can frequently overpower the kinesthetic feedback students feel in their bodies and must learn to interpret.” She quotes Montero here: “a trained dancer often trusts proprioception more than vision.” I’m reminded that every time I perform, I do so without glasses, frequently in unfamiliar spaces, with the worst eyesight of anyone I personally know. The term proprioception is new to me, but the concept of this “sixth sense” feels true to my experiences.

I’m finding that both the teaching and performance of Sri Lankan dance nowadays have, for myriad reasons, moved towards a greater emphasis on aspects of line, form, precision, as if the ideal of dance is primarily visual. The purpose of this post is not at all to knock mirrors as aids in dance practice, but to promote and explore other traditional modes of learning, understanding, and interpreting movement which do not privilege sight over other senses.

Sources

Raddell, Sally. “Mirrors in the Dance Class: Help or Hindrance?” IADMS.

Reed, Susan. “Women and Kandyan Dance: Negotiating Gender and Tradition in Sri Lanka.”